Who was Queen Boudicca and what was her style of jewellery?

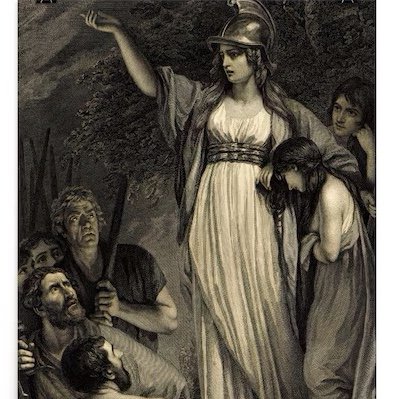

“She was huge of frame, terrifying of aspect and with a harsh voice. A great mass of bright red hair fell to her knees…..”

Boudicca, also called Boadicea, was queen of the Iceni tribe, the Celtic people who inhabited the northern part of East Anglia at the time of the Roman invasion two thousand years ago.

Her husband Prastutagus, the king of the Iceni, had agreed to become a client king of the Roman invaders in return for being left to run his kingdom with only minimal Roman interference. When he died, he made the mistake of leaving half his kingdom to his two daughters and the other half to the Roman emperor – perhaps hoping this would win favour for his family and tribe.

Under Roman law, daughters could not inherit so the Romans decreed that all should pass to the emperor. When Boudicca tried to challenge this she was whipped like a common slave and her daughters were beaten and violated. This enraged Boudicca and the Iceni and thus the revolt which killed thousands and frightened mighty Rome, master of the known world, was begun.

Neighbouring tribes including the Trinovantes had long resented the presence of the Romans and quickly joined the huge army 100,000 strong, gathered together by Boudicca. She led them first to Camulodunum (Colchester) where Romans and their sympathisers were slain in their thousands and then on to Londinium (London) where again there was huge slaughter. It is said the entire Ninth Legion was wiped out. The Romans had not seen the revolt brewing and were anyway concentrating on fighting the Druids on the isle of Mona (Anglesey). They were very nearly defeated and driven out of Britain altogether, rocked by the ferocity of Boudicca and her followers.

The Romans rallied however and fought back. Boudicca’s army might by now have numbered nearly a quarter of a million – but superior Roman discipline and organisation eventually triumphed and an outnumbered Roman army defeated Boudicca in a battle which probably took place somewhere in the Midlands. Rather than being taken by the Romans, it is said Boudicca killed herself and her daughters. The Romans stayed in Britain for another 400 years leaving Britain ready for her next, perhaps better known and better loved hero – Arthur. Arthur may or may not have been real, but Boudicca most certainly was real. Some say she is buried in London under platform 13 of Kings Cross station…. Many say her ghost rides her chariot through Norfolk and Suffolk even now…

The Celts emerged within the Iron Age, which heralded a new wave of working techniques and materials, namely iron and steel, which required forging and working rather than simply casting. These new innovations gave rise to weapons, jewellery, utensils and armour which were lighter and stronger than during the previous Bronze Age.

IRON AGE JEWELLERY

The Torc

One of the most distinctive and notable items of Celtic, Iron Age jewellery is the metal torc, which in basic terms is a simple neck ring, otherwise known as a traditional Celtic necklace. Examples range from basic, undecorated iron rings, to elaborate twisted gold versions with cast, decorated terminals at either end. One of the finest examples was found in 1950 in Snettisham in Norfolk and has since become known as the Snettisham Great torc.

This particular torc was made from Electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of Gold and Silver). The main body of the Celtic torc was constructed from eight twisted strands of electrum, which were each made from another eight strands. The elaborate terminals at each end are hollow and cast with additional chased detail that would have been soldered on.

There is strong evidence to suggest that torqs were worn by all levels of society, particularly by women. But historians also believe that torqs were worn as battle dress too.

Who Wore Celtic Torcs?

Archaeologists have found Celtic torcs in the graves of both men and women, but the biggest and most beautiful in Europe were of course in the burials of wealthy nobles. I wonder given they were made in a variety of metals and sizes if they were a standard style of jewellery and the cut of your torc denoted your status in society?

Some torcs were rather elaborate and were very decorative as seen below. This torc would have been made for a very important person!

There is strong evidence to suggest that torqs were worn by all levels of society, particularly by women. But historians also believe that torqs were worn as battle dress too.

Celtic torcs have been found in graves in Europe so archaeologists can work out how they were worn and who wore them from their context. However, all the torcs discovered to date in Britain have been in treasure hordes, so they lack any human context at all. Were they buried in graves that have not been found yet or were they passed down as heirlooms rather than buried with their dead owners? Julia Farley of the British Museum suggests owning a repaired heirloom torc could be a status symbol perhaps the ancient Britons considered them too valuable to inter with the dead? As a people famous for giving extravagant metal offerings to their gods it could be these hordes were offerings?

The Celtic jewellery smiths would use sheet metal to make a doughnut then put a mandrel in the centre to make the hole. They secured this onto the neck ring with a gold collar to hide the join. Sometimes this was soldered which sounds simple, but it is challenging to solder a delicate hollow piece onto a sizeable solid section, you have to keep it all at the same temperature and not melt bits of it! One Celtic torc they investigated seemed to be cold joined, and the terminals were secured using closely fitting rods.

The torcs were made from thin lengths of metal normally a mixture of gold and silver for the rich or just a base metal like iron for normal folk.

The lengths of metal would be secured together at one end and then twisted to make one of the thicker ropes of metal. These would then be twisted together in twos or threes of the twisted ropes to make one even thicker rope. These would all be secured together either by soldering which would be tricky or cold joining as previously mentioned!

The Brooch

One of the most universal pieces of Celtic jewellery was the brooch. Celtic brooches have been found in burial sites across Europe and served both functional and decorative purposes as the Celtic jewellery was used as a cloak fastener on one or sometimes both shoulders. Examples have been found in gold, silver, iron and bronze. Most were cast and included a safety-pin mechanism, which is often used to date pieces, as it evolved over time. Subjects for brooches were varied, but a favourite theme was animals depicted as a whole or simply the head.

Bracelets

Other popular items of Celtic jewellery included bracelets, which were worn on each wrist, anklets, again one on each ankle and also armlets.

Bracelets looked like mini torcs or were just plain bands of metal rather like bangles.

Rings

Depending on the status of the wearer most rings were simple bands of metal for the poorer folk whereas more elaborate designs were made for the noble folk. Some of these rings had glass chips as decoration. Other rings were rather like the modern day signet ring with engraved designs on the front.

Toe rings were popular too as well as rings to decorate women’s hair!

A gold Iron Age hair ring.

Although some of the Iron Age jewellery looks very basic, certain skills and tools to make the pieces must have been researched, designed and manufactured to produce such skilfully made items such as the torcs.

This all took place in the times just before and after the birth of Christ. So the craftsmen would be without technology, electricity hence having to work in daylight hours.

A piece of (as I found) horrifying humour!

The other evening I went out into our back garden and there in front of me on the patio was this…

Someone suggested that I could wear it as a torc! I could see why because of its shape and texture and colour of its skin!

I don’t think so as I absolutely hate slowworms!